NOTE: Original post in Swedish here

Jana Kippo, a woman in her mid-30s, has returned home after many years away to Kippogården in the fictional village of Smalånger in Västerbotten. She wants to help her twin brother, who is drinking himself to death.

In SVT:s adaptation of Karin Smirnoff’s book ”Jag for ner till bror” (“I Went Down to My Brother”), Jana Kippo is brilliantly portrayed by Amanda Jansson in what I think is some of the most authentic acting I’ve seen in a long time.

Rasmus Johansson plays Bror with such raw vulnerability that it fills the entire room.

The screenplay is written by Karin Arrhenius, and the series is directed by Sanna Lenken. I have to admit it feels incredibly refreshing to watch a TV series set in genuine rural Sweden, with grounded, realistic characters completely free of glitter, glamour and contrived superficiality. At Kippogården there is old ingrained dirt, barn muck, potato peelings, greasy hair and unmade beds in a house that no one has cared for in many years.

The set design by Betsy Ångerman Engström is done with great credibility. The embroidered cross-stitch sampler with moose or deer (see image further down) is just one detail among many that shows a highly developed sense of touch.

I am a retired journalist who write blog posts and makes podcasts.

NOTE! NEW SWISH NUMBER: 123 519 92 86

Bankgiro 111-9072

From abroad: IBAN number SE 19 6000 0000 0004 8212 9581

Swift-BIC code HANDSESS.

Warm thanks for your donation!

A total absence of beauty and grace

It’s not just the ugliness and grey shabbiness. It’s a complete and merciless absence of beauty and grace. The stark, laconic Västerbotten dialogue, the unvarnished kitchen-sink realism – much of it is probably recognizable to many of the 1.5 million people who have watched the series so far and who don’t feel at home in polished, artificial big-city dramas.

“I wasn’t alone. I had the pine trees”

The series revisits a Västerbotten previously described by literary giants such as Sara Lidman (1923–2004), Torgny Lindgren (1938–2017), and Per Olov Enquist (1934–2020).

About his childhood, Enquist wrote in 2007 – a quote that sums up much of Västerbotten’s loneliness and barrenness:

“If you are born deep in a forest, trees and ground are safety. I had no playmates, but a large forest all to myself – that created my strong and unbreakable character. I wasn’t alone. I had the pine trees.”

The strong bond between two siblings who have lived through hell

Between Jana Kippo and her twin brother there is a powerful bond, forged during a hellish childhood with a tyrannical sadist of a father – called Fadren – who threatens and beats his wife, psychologically and physically abuses his son, and repeatedly forces himself sexually on his daughter Jana in incestuous assaults.

The children’s life under the tyrant is unbearable, and the mother, herself a victim, cannot protect them. It is the boy Bror who ends the torment by killing the father with a spade.

The inner torment remains, and Bror drowns it in alcohol

But the inner torment remains, and Bror drowns it in alcohol.

Jana takes him to an AA meeting (Alcoholics Anonymous). The following lines come from the AA meeting when the two siblings introduce themselves and are welcomed. In all their terse brutality, they sum up the essence of the entire series for me.

“Bror Kippo. Alcoholic.”

“Jana Kippo. Relative.”

“Welcome here. Jana, would you like to tell us a little about yourself?”

“Nah. Mostly that I’m Bror’s sister.”

“Is there anything you want to tell us about Bror?”

“Besides him being an alcoholic, you mean? He’s good with animals. They’re alike, him and the animals. And I want to say that he killed our father with a spade.”

“Why did he kill your father with a spade?”

“Because no one else did anything. Everyone knew what was going on but did nothing anyway. So we had to take matters into our own hands, so to speak. Even though we were only children.

We were only children.

But the main thing I want to say about Bror is that I like him. That he is my everything. Half my soul.”

The rock-solid relationship between two siblings

I think these lines more than anything else show that the SVT series is above all a portrayal of the rock-solid relationship between two siblings, of love, loyalty and solidarity. It is the image of two who when they are born already have lived together for nine months, close to each other, and who know each other inside and out.

“He is my everything. Half my soul” Jana says at the AA meeting.

It is beautiful.

“Sibling relationships follow us through large parts of life”

Sibling love – when do we talk about it? Surprisingly seldom. For most people, other loves in life become more important than the love for the person you have known since birth. But sibling relationships are the longest and strongest relationships we have. They follow us through large parts of life – often for 80 or 90 years or even longer.

With siblings we share frames of reference, experiences of our parents and of ourselves and each other as the people we have been and are. Nothing needs to be explained. Siblings already know everything. The memories are largely the same.

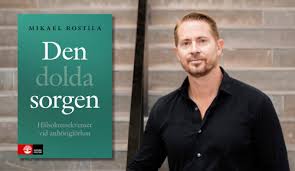

“Because most siblings live together during childhood and share upbringing and everyday life with each other, a strong emotional bond is created that resembles the attachment to parents” writes Mikael Rostila, professor of public health science and associate professor of sociology, in the book ”Den dolda sorgen: hälsokonsekvenser vid anhörigförlust” (“The Hidden Grief: Health Consequences of Losing a Loved One”).

”The strong sibling relationship established in childhood often continues into adulthood, meaning siblings constitute an important source of emotional and practical support throughout life. Therefore, losing a sibling – in childhood or adulthood – brings deep grief and longing.”

Our place in the sibling order often shapes us for life

Psychological research shows that our place in the sibling order often shapes our personality, health, and career choices throughout life. The eldest child is often responsible, well-organized, ambitious, and dutiful.

Eldest siblings are overrepresented among managers and business leaders. They can experience higher stress levels and have a higher risk of heart attack.

Middle children, who learn to adapt in all directions, become good at handling conflicts and often flexible mediators.

The youngest child is often charming, adventurous, and creative. Can be perceived as less responsible. Younger siblings tend to have poorer physical health (more hospital care) compared to firstborns.

How do you manage without siblings?

I have and have had several friends who are only children, and while I understand that it can have its advantages, another feeling has weighed heavier for me: compassion for those who have not had any siblings to share origins, memories, joys, sorrows, and life with. How do you manage without siblings?

At the same time, I have gained insight into adult sibling relationships marked by discord, seemingly insoluble conflicts, estrangement, separations, and strong feelings of hatred and alienation. Underlying conflicts are often triggered in connection with inheritance settlements. How the parents’ estate is divided becomes a measure of which child the parents loved the most.

The consolation is that many conflicts – though not all – can be resolved and worked through. There is expert help available, both legal and psychological, and one should not hesitate to seek it if stuck.

“Nothing has happened to my brother since a Sunday morning in July 1912”

“While I was down in the pasture with the cows, my brother was prepared. When I came back during the day he was no longer in the bed. He had been carried up to the attic. We would never again lie in the same room, he and I. He would lie in the attic.”

The quote is taken from Vilhelm Moberg’s (1898–1973) book ”Din stund på jorden” (“Your Moment on Earth”) from 1963, where he describes the day he lost his older and only brother, Sigfrid. Vilhelm Moberg is only eleven years old when he loses his brother. He looks back on what their relationship has been like through life, but also how it has frozen in time.

“Where the dead are, there is no more time. Sigfrid remains in a room he entered fifty years ago. He is unreachable. Nothing has happened to my brother since a Sunday morning in July 1912, when the clock was twenty minutes past seven.”

As if by coincidence, Vilhelm Moberg chose exactly the same time to end his own life 61 years later. He was deeply depressed and drowned himself on the morning of August 8, 1973, in Väddöviken outside his house in Söderäng on Väddö in Roslagen. Earlier that same morning he had finished a letter to his wife with the words:

“The time is twenty past seven. You can find me in the sea, the sleep without end. Forgive me, I could not endure.”